In the 17th and 18th centuries, coffee wasn’t just a beverage—it was a cultural force that helped shape the modern world. During the Age of Enlightenment, when Europe experienced a surge in philosophy, science, art, and political thought, coffeehouses became the unofficial headquarters of intellectual and social revolution.

This article explores how coffee played a surprising yet powerful role in transforming Europe, encouraging new ways of thinking, and even challenging old systems of power.

A New Kind of Drink for a New Kind of Thinking

Before coffee became popular in Europe, alcohol—especially beer and wine—was the most common daily beverage. Even breakfast often included weak beer or diluted wine. Water was unsafe in many cities, and alcohol was the safer, more accessible choice.

Then came coffee—a stimulating, non-alcoholic drink that sharpened the mind instead of dulling it.

Coffee arrived in Europe in the 1600s via trade with the Ottoman Empire and quickly gained popularity among the educated elite. Unlike alcohol, it invited clarity, energy, and focus—perfect for reading, writing, and debate.

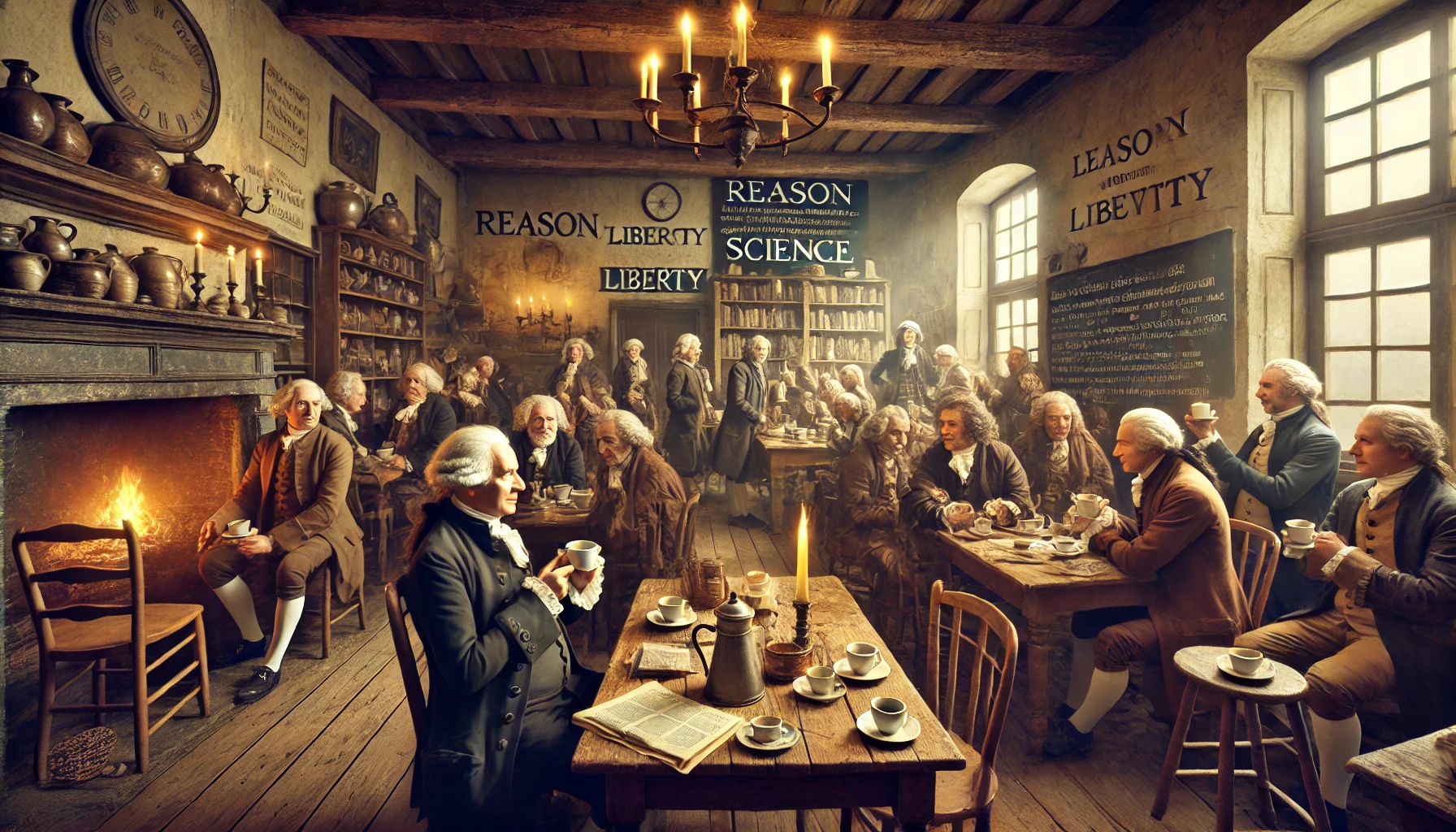

The Rise of the Coffeehouse

The first European coffeehouse opened in Venice in 1645, and by the late 1600s, they were flourishing in cities like London, Paris, Vienna, and Oxford.

These weren’t like modern cafés. They were lively, loud, and packed with philosophers, poets, scientists, businessmen, and revolutionaries. People came to drink, read newspapers, share ideas, and argue over politics.

What Made Coffeehouses So Powerful?

- Accessible to many social classes (not just elites)

- Encouraged public discourse and debate

- Provided access to books, journals, and pamphlets

- Became hubs for scientific and political innovation

So influential were these spaces that French writer Voltaire was said to consume up to 40 cups of coffee a day while working at his local Paris café.

Penny Universities: Coffee and Education

In England, coffeehouses became known as “penny universities”—for the price of a penny (the cost of a cup), you could sit and listen to conversations as stimulating as a formal lecture.

These spaces offered access to ideas, information, and diverse perspectives—a vital part of Enlightenment thinking. They democratized knowledge in a way that was radical for the time.

Notable thinkers like Isaac Newton, John Locke, and Jonathan Swift were known to frequent coffeehouses, often using them as informal classrooms, meeting spots, or think tanks.

Coffee and the Spread of Newspapers

Many coffeehouses were closely tied to the rise of journalism and publishing. Patrons would gather to read and discuss the latest news, political pamphlets, or essays.

In some cities, coffeehouses acted as unofficial distribution centers for newspapers. The availability of printed information and free discussion helped accelerate the Enlightenment’s spread of rational thought and skepticism.

Challenging Authority and Tradition

Not everyone welcomed this new coffee culture. Governments and religious leaders worried about the subversive nature of open discussion and the possibility of rebellion.

Some rulers even tried to ban coffeehouses:

- King Charles II of England attempted to shut them down in 1675, calling them centers of “idle and disaffected persons.”

- The Ottoman Empire banned coffee multiple times due to its association with political dissent.

- Clergy in Italy debated whether coffee was a sinful or Muslim beverage (until Pope Clement VIII famously “baptized” it).

Despite resistance, the movement grew—and coffee became a symbol of progress and challenge to the status quo.

Coffee and Revolution

The Enlightenment ideals that percolated in coffeehouses—reason, liberty, equality, and secularism—helped shape the major political revolutions of the era.

French Revolution

In France, coffeehouses were hotbeds of political discussion leading up to the French Revolution. Citizens gathered to read radical pamphlets and debate royal authority.

American Revolution

In the American colonies, cafés and taverns (often serving coffee) became meeting spots for the Founding Fathers. The Boston Tea Party helped fuel a shift from tea to coffee as a symbol of American independence.

Coffee became the drink of choice for revolutionaries, rebels, and reformers.

Final Thoughts: A Cup That Changed the World

Coffee wasn’t just a drink during the Enlightenment—it was a catalyst. It sharpened minds, fueled conversations, and gave birth to new ways of thinking. It helped shift Europe from superstition to science, from monarchy to democracy, and from tradition to innovation.

So the next time you sip your morning brew, remember: that cup carries a legacy of bold ideas, brave voices, and a better future—brewed in the back rooms of coffeehouses and stirred into history.